Michael Moyles' Story

Like my father, I always loved basketball. I was never very good -- but by 1998, I was able to hold my own enough to win a small city-league championship in south St. Louis, near where I was stationed as a Captain in the U.S. Air Force. The following year, our team was in the midst of the playoff semifinal, hoping to defend our title. In a freak accident, I dove for a loose ball at precisely the same time as an opposing player, colliding head-first...when I woke up about 30 seconds later, I couldn't move my right arm, and lay motionless on the court until an ambulance arrived. The days that followed would forever change my life. I was sent home from the hospital later that evening, after a CT scan and other tests showed no serious injury other than a good concussion and a pinched nerve partially disabling my right arm -- both conditions that would heal in a few weeks. As a precautionary measure, I was scheduled for an MRI the following day, which would reveal any additional damage to the soft tissues in my head and neck.

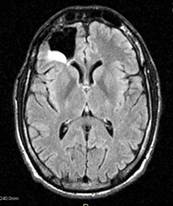

An MRI is an intimidating experience -- especially if you're claustrophobic. Confined in a tube about two feet in diameter, with a helmet holding my head motionless, I could only see out the tube, between my feet, through a small mirror directly above my eyes. My world for those 45 minutes was the mirror in front of my face, revealing two size twelves and a technician behind a bank of monitors. As the test concluded, the technician picked up the phone, and another officer arrived -- I guessed a doctor simply by his rank -- then another. Then a third, this one a Colonel, likely the Chair of either the Department of Neurology or the Department of Radiology. I watched with increasing apprehension as the team gathered around the monitors, staring at what I assumed were images of my brain -- pointing, gesturing. When I was finally brought out of the MRI tube, the only one left was the Colonel. He sat down next to me and said those words I'll never forget: "Mike, we've found something." More scans. More tests. Immediately transferred from the base clinic to Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the largest and best hospital in the city. The basketball injury was now a distant second priority and soon just a memory, as doctors from all over the city tried to discern what was on the MRI -- a lesion, a birth defect, a cyst, a tumor -- each successive doctor had a different diagnosis. Finally, after almost a year of doctors, tests, scans, hospitals, and every diagnosis you can imagine, the neurosurgical specialty clinic at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles settled on a diagnosis -- astrocytoma. Brain cancer. I was 27.

A few months before the basketball injury that exposed the cancer, I had proposed to my girlfriend, Angie. Despite turning me down the first four times I asked her out, she said "yes" to the first proposal, and we got engaged. Accepting the proposal of a healthy, young, strong, up-and-coming Air Force officer, she now found herself engaged to a terminally ill cancer patient. Unfortunately, the prognosis was not good -- six years, maybe eight with treatment. Undaunted, she remained completely committed, and we were married in April of 2000, less than six months after my initial diagnosis. Treatment options for brain cancer are limited. Mine was WHO Grade II, so surgery was the primary option. On the eve of my first wedding anniversary -- April 28th, 2001 -- I was admitted to the Maxine Dunitz Neurosurgical Institute at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, where Dr. Keith Black and his top team of neurosurgeons removed a 2.8-cm tumor from my right frontal lobe, just above and behind my right eye. The right frontal lobe is primarily responsible for memory, personality, and language, yet amazingly I experienced no neurological deficits. Recovery was long and slow, but within six months I was essentially back to normal (well...back to my old self, anyway).

Remission is a funny thing. Far from comfortable, remission leaves you feeling something in between apprehension and expectation -- afraid the cancer is going to return, and almost expecting it to. Whatever it is, remission is rarely permanent. In my case, it lasted almost four years. Brain cancer is normally tracked with serial brain scans, and I had scans every 90 days, then every six months, then after two years of clear scans, I went to annual scans. The second annual scan in the spring of 2005 showed significant recurrence -- the cancer was back, and back with a vengeance.

Larger, faster-growing, and more aggressive, this time we couldn't watch it for a year to see what it was doing, and I was back at Cedars-Sinai within a month. Almost four years to the day -- this time, on my fifth wedding anniversary -- I went in for surgery number two. The surgery and recovery were similar to the first time, but because the tumors had proven to be recurrent, the Cedars team recommended chemotherapy. This is a word that will strike fear into the heart of even the most hardened patient, and I was no exception.

After numerous meetings with oncologists and neurosurgeons, I began chemotherapy just a few days after returning home. I had no idea what to expect -- I'd heard stories of chemo patients curled up in a fetal position with a bucket for days on end, yet I'd been told of other patients who continue to live and work normally while going through chemo. Where would my experience fall between the extremes? Well, somewhere in the middle. Chemo is a full-time battle of symptoms and side-effects -- chemo makes you nauseous, so they give you an anti-emetic, which makes you constipated, so they give you a stool softener, which...well, you get the idea. In twelve months of chemo (a 28-day cycle of five consecutive days of chemo followed by a 23-day recovery period), I was actively sick two or three times.

But something else happened during my first few rounds of chemo. I found that exercise -- specifically, running -- helped manage the symptoms as much as anything else. Even better, being in shape put me in a better position to fight what was quickly becoming the battle of my life, and the battle FOR my life. It wasn't long before I decided to find a local marathon and prove that cancer couldn't keep me down. I ran and trained all through chemotherapy, and finished by first marathon between my tenth and eleventh rounds.

Unfortunately, the cancer returned less than a year after I finished chemotherapy. Using the rationale that the cancer remained at bay during chemo and returned when I stopped, oncologists decided the best thing to do would be to go back on chemo. Another twelve rounds -- another year. Over the next ten months, I completed ten more rounds, two more marathons, watched my wife give birth to our beautiful daughter, and listened to the doctor tell me that the cancer had continued to progress during chemo. The oncologist concluded that I was a "chemo failure" -- the cancer had developed a resistance to it. The only option at that point was to go under the knife again, for surgery number three, in December of 2008.

Surgery alone had failed. Surgery followed by chemotherapy had failed. Now in a clinical trail at the National Institutes of Health, the experts there hit the cancer with a triple-punch -- surgery, followed by combined chemotherapy and high-dose radiation. For 42 consecutive days, I made the hour-long trip up to NIH, where I lay motionless for 40 minutes as a large machine radiated my brain from every direction, hoping to destroy any residual malignant cells that hadn't already been removed by surgery or genetically altered by chemotherapy. Radiation and chemo are very different things, and the side-effects are completely different. There was no nausea or vomiting with radiation, but the fatigue is overwhelming. I also lost my hair (I didn't have much anyway), but made it through the treatment without major problems. The major problems started a few months later. After a long run, my hat wouldn't fit. Within a few hours, my right eye was swollen shut. A trip to the emergency room turned into a 40-hour marathon session, culminating with admission to the hospital with osteomyelitis, a dangerous infection in the bone that is most dangerous in the skull. If the infection was able to get into the brain, encephalitis could follow. I was admitted to the National Naval Medical Center for a cranioplasty, where neurosurgeons would remove any portion of the skull that was infected. Once the infected bone was removed, I was fitted with an IV port in my upper arm, and treated for six weeks with IV antibiotics to prevent the infection from spreading. Life without a forehead is interesting to say the least, if for nothing else than the looks and questions it generates. I was supposed to wear a helmet during the six months I was forehead-less, but usually just ended up with a hat instead. Six months after my forehead was removed and the infection treated with antibiotics, I went back for surgery number five, this time to replace the frontal plate with an acrylic prosthetic. Surgery went without a glitch, and the "triple punch" of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation seems to have knocked the cancer down for now. The infection is gone, the prosthetic plate is fine, and my last three brain scans have shown no sign of recurrence. I know that remission is usually a temporary thing, and I'm ready to fight whatever comes next. Every morning after I wake up, I think, "Cancer may one day take my life. But not today." Every run is my way of proving that it hasn't gotten me yet. I'm still running marathons and half-marathons, now focused on raising money for brain cancer research.

FIGHTING THROUGH FITNESS is the culmination of ten years of fighting cancer, running marathons, and raising money, now combined with the support of friends and family. FIGHTING THROUGH FITNESS represent everything I've been through and fought for over the past decade. We are here to help you with your fight, be it Cancer or some other disease, depression, weight loss, addiction, or simply wanting to be as fit as possible, FIGHTING THROUGH FITNESS is in your corner.